As veterinary dental and oral surgery specialists we are often asked about anesthesia. Many pet parents will express their concern for their pet’s safety during anesthesia. Some of them will have had previous bad experiences or have friends that have had bad experiences with anesthesia in both their human and non-human family members.

Our doctors at Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals are required to have additional anesthesia training above and beyond the routine veterinary training. We continue that training endlessly throughout our careers by attending lectures and seminars, as well as interacting with other veterinarians who are board certified in veterinary anesthesia.

Appropriately, our referring doctors often refer patients to us because of the increased risk of anesthesia due to comorbidities (additional medical issues), therefore we have much experience in dealing with nearly every scenario imaginable.

Speaking of comorbidities, age is not one. Typically, in the healthy patient, there is no increased risk from one to 12 years of age. After 12 years of age, we typically just need to lower our dosages a bit. It is never correct to say this pet is too old to anesthetize. Doctors at Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals routinely and successfully induce anesthesia on very old geriatric dogs and cats.

We jump through many hoops to reduce the risk of anesthesia. The first step is when one of our doctors carefully reviews your pet’s complete medical history. Age, breed, species, comorbidities, current medications, and presenting issues are all taken into account to formulate an individualized plan. It is not often that the same protocol is used on different patients. The pet’s parent is also asked for more information…often the parent’s insights are invaluable because no one knows the pet better than the parent.

After a complete and detailed review of the medical history and speaking to the pet’s parent, a thorough and complete physical examination is performed. (FYI it is often said that it takes four years of veterinary school to perform a five-minute physical examination.). If other challenges are identified on the physical examination, they will often need to be addressed prior to the anesthetic procedure, thereby lowering risk even more.

It is not infrequent that after speaking to the parent, reviewing the medical history, and performing a physical examination taht we order additional tests and examinations to further decrease risks. For example, it may be necessary to have the patient examined by a cardiologist before we formulate an anesthetic plan. We do see a large number of patients, some older, some younger, with heart disease.

A cardiologist’s evaluation will typically tell us one of four things:

- Proceed as planned. No additional precautions are recommended.

- Proceed, but use and/or do not use these particular medications along with other suggestions and cautions.

- Only proceed under the direction of a veterinary anesthesiologist.

- Very rarely the cardiologist will suggest to not proceed because the risk is too great.

It is appropriate here to define “veterinary anesthesiologist.” A veterinary anesthesiologist is a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine who has completed a 12-month internship or equivalent practice experience, and then completed a three-year intensive training program referred to as a residency.

After successful completion of the residency, the candidate must take and pass a rigorous three-day examination. When all criteria are met, their official title is Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia (DACVAA)…aka board certified veterinary anesthesiologist. These doctors are the undisputed experts in veterinary anesthesia and analgesia. Because most veterinary anesthesiologists use gas anesthesia, we like to tease them by affectionally referring to them as “gas passers”.

Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals has a veterinary anesthesiologist on staff, Dr. Martin Kennedy. Dr. Kennedy will review the medical record, speak to our doctors and technicians, and then formulate an individualized plan for that patient. If needed, he has the capability to remotely view the anesthetic monitor (vital signs) in real time and make suggestions. This is an incredible and invaluable benefit for our patients.

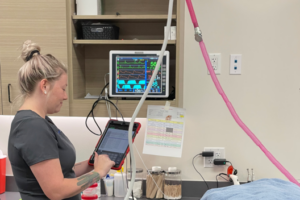

A photo of our newest technology monitor in use. Parameters being monitored are EKG, Oxygen Saturation, Pulse Rate, Expired CO2 , Respiratory Rate, Blood Pressure, and Body Temperature.

When the patient’s individualized plan has been formulated, a sedative is administered by injection. The patient typically becomes very relaxed and happy. It appears that most patients really enjoy these medications.

Shelbi using her expertise to monitor a patient under general anesthesia. Note the sheet taped to the counter. It shows the dosages and volumes of every possible emergency drug calculated for that individual patient.

Once the sedative has taken effect, an IV catheter is placed, and IV fluids are started. The rate of IV fluids is dependent on the individual’s health status. Obtaining a baseline blood pressure and EKG is done before inducing anesthesia. Pure oxygen is administered via mask for a minimum of five minutes. After pre-oxygenation, the doctor then administers an IV medicine that induces sleep. This stage is referred to as induction. An endotracheal (breathing) tube is placed to protect the airways. After induction, another blood pressure measurement is immediately taken. The pulse oximeter and temperature probes are placed. Each patient is assigned their own veterinary technician that continuously monitors and records the vital signs. An anesthesia chart is generated that includes all the medications used, interventions, and monitoring of vital signs every five minutes.

During the procedure, each patient has a minimum of three humans attending them at all times: the anesthesia technician, the surgical/dental technician, and the doctor. (Some patients require more than three humans attending them.)

The goal is to provide light anesthesia. That is all that is usually needed in dentistry and oral surgery. If a painful procedure is to be performed, nerve blocks are used to numb the patient (often for three days). In addition, most of the drugs used have “reversal” agents that can be used if necessary to stop the effect of the anesthetic medications.

It is very important to maintain a proper body temperature. Animals, including the human animal, often cannot maintain adequate body warmth during general anesthesia. The team at Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals is very skilled at maintaining safe body temperatures. Our patients lay on a pad that has warm water circulating through it. Lying on top of the patient is a pillow that has warm air blowing through it from a device called Bair Hugger. The patient’s head and mouth are a source of heat loss; therefore the head is wrapped. In addition, the core body temperature is continuously monitored and recorded every five minutes. If needed, adjustments can be easily made to the care plan.

After the procedure, the patient is closely monitored to help them wake. Waking from anesthesia is referred to as “recovery”. All parameters continue to be monitored. When the patient’s reflexes return (we wait until they swallow and can breathe on their own), the endotracheal tube is removed (extubation). Monitoring continues after extubation to ensure respiration and oxygen saturation are within normal limits.

Many patients will be a bit fatigued post-anesthesia. The author recently had a short anesthetic procedure with short-acting medications and was fatigued for three days. Our four-legged family is no different. Typically, the younger and healthier the patient, the quicker the recovery to normal.

It is not uncommon for animals, including humans, to be a bit nauseous after anesthesia. All of the patients at Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals are administered an anti-nausea medication, however, sometimes nausea still occurs. The take-home point here is to know that your beloved pet will likely be a bit “off” for a day or two. As mentioned above, the two-year-old patient may be normal in a matter of hours versus a 15-year-old patient that may take a day or two to bounce back.

Fear of anesthesia, although not always justified, is real and is to be respected. Often the risk of not performing a comprehensive oral health assessment and treatment carries more risk than anesthesia.

Kipp J. Wingo, DVM

Diplomate, American Veterinary Dental College

Carefree Dentistry & Oral Surgery for Animals